who cares if languages become extinct?

February 20, 2009

UNESCO reports that 2,500 languages are threatened with extinction. As reported, it is easy to have an immediate reaction of horror as the word extinction evokes a loss of a living species. In fact “languages are undergoing a global extinction crisis that greatly exceeds the pace of species extinction,” said David Harrison, a linguistics professor at Pennsylvania’s Swarthmore College (via nationalgeographic.com). However, some people hear this news and wonder “Is language extinction a good thing?” After all, wouldn’t it be easier if we could all communicate using the same language? isn’t language extinction just part of language evolution? In addition to being natural, it helps communication. Shouldn’t we do everything we can to hasten this trend in the name of world peace?

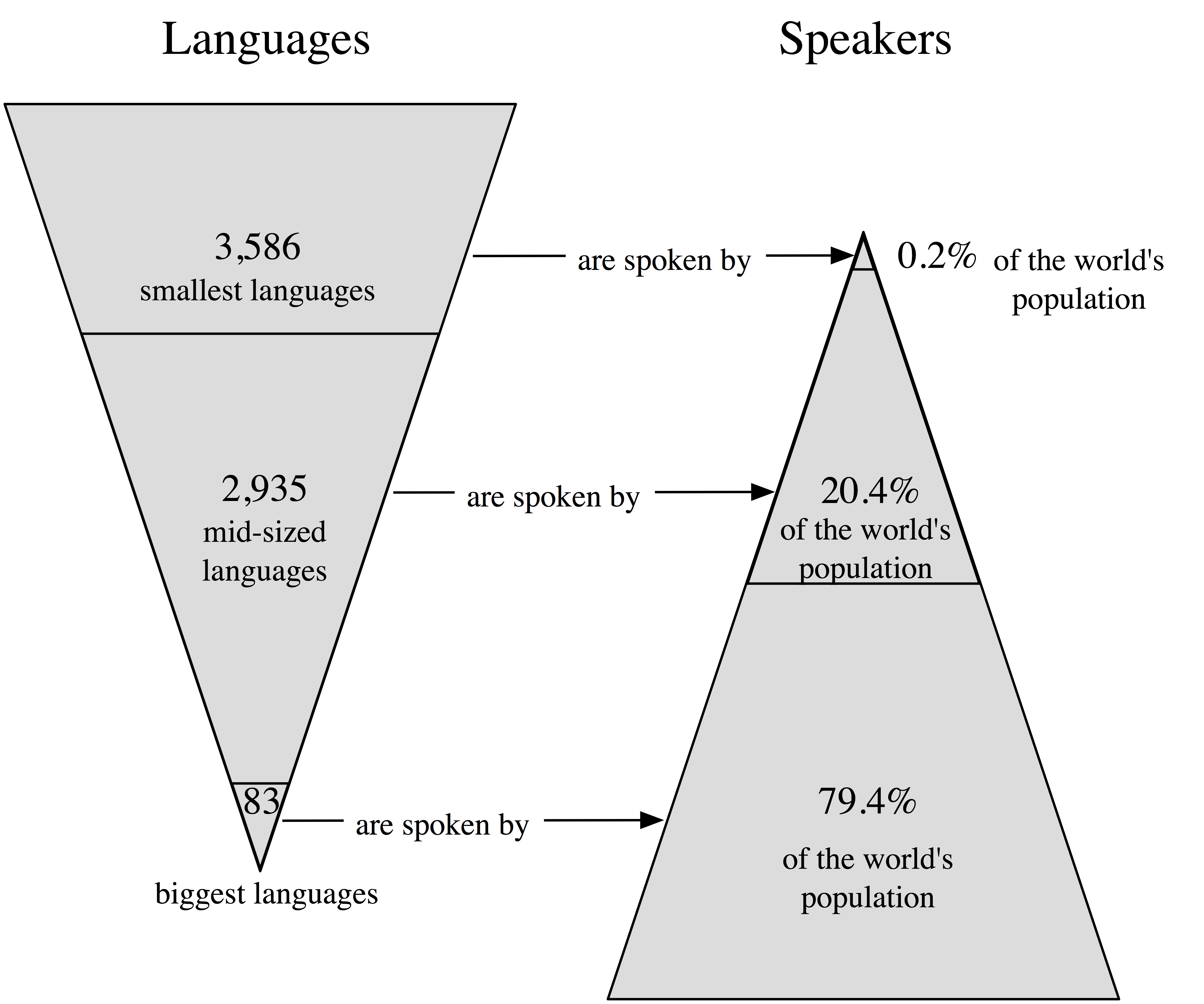

source: Global Language Trends, Swarthmore College

Actually, it’s not exactly natural for people in diverse ecosystems to speak identical languages. We have different things to describe based on location and specialization, it makes sense that we would have different words, even different grammar, to describe our uniqueness.

“We live in the digital age and we like to imagine… we have this kind of fantasy… that any information that is useful is available to us somewhere in writing, in some book or library or database or it can be googled. That’s not true, and, in fact, we’re facing an immense knowledge gap. Most of the world’s languages have never been written down anywhere. They have not been recorded. They have not been adequately documented from a scientific point of view. And so, as they vanish, we will have, literally, no record of them and all of the ideas and thoughts and technologies that they contain.” — Dr. K. David Harrison, Living Languages Digital Dialog

So why can’t we just translate all of this great knowledge into English or Mandarin? Why keep the language alive? Harrison has an interesting response:

And it’s true, I could take a word like, “ederre” in their language, which means a 4-year old, male, un-castrated, domesticated, ride-able reindeer. And I can express that concept in English. I just did. But, languages are the product of millennia of fine-grained and sophisticated observation and packaging of information into hierarchies and taxonomies. Any of you that have ever gotten a million hits for your Google search and have been frustrated by that result, understand the value of structured information, of folksonomies. These languages are like trees. They organize information. When people shift over to speaking global languages, it all gets flattened out into a puddle.

Harrison also makes the argument that preserving these languages is related to preserving species and ecosystems. He describes the language of the Yupik of Alaska as a “technology” which aids them in hunting and in surviving in one of the harshest environments. Perhaps their ability to name, and thereby precisely distinguish 99 different formations of sea ice is also one of the most sensitive instruments to detect the signs of climate change and global warming. Maybe Western scientists should spend less time “discovering” and more time listening and collaborating with people who have these specialized skills encoded in their language.

source: Living Languages Digital Dialog

source: Living Languages Digital Dialog

National Geographic also quotes Harrison on the same topic:

“When a language is lost, centuries of human thinking about animals, plants, mathematics, and time may be lost with it…Eighty percent of species have been undiscovered by science, but that doesn’t mean they’re unknown to humans, because the people who live in those ecosystems know the species intimately and they often have more sophisticated ways of classifying them than science does,” he said. “We’re throwing away centuries’ worth of knowledge and discoveries that they have been making all along.”

In Bolivia, Harrison and Anderson met with Kallawaya people, who have been traditional herbalists since the time of the Inca Empire.

In daily life the Kallawaya use the more common Quechua language. But they also maintain a secret language to encode information about thousands of medicinal plants, some previously unknown to science, that the Kallawayas use as remedies.

The navigational skills of peoples in Micronesia, meanwhile, are similarly encoded in small, vulnerable languages, Harrison said.

“There are people who may have a special set of terms … which enable them to navigate thousands of miles of uncharted ocean … without any modern instruments of navigation.”

Harrison concludes his talk, Living Languages Digital Dialog, by saying that giving up linguistic diversity is a “false choice of globalization… we would all be better and smarter if the world remains multilingual.”